Gift this article

In this Article

Follow

Have a confidential tip for our reporters? Get in TouchBefore it’s here, it’s on the Bloomberg Terminal LEARN MORE

September 2, 2024 at 23:31 GMT+7

Save

Listen

4:18

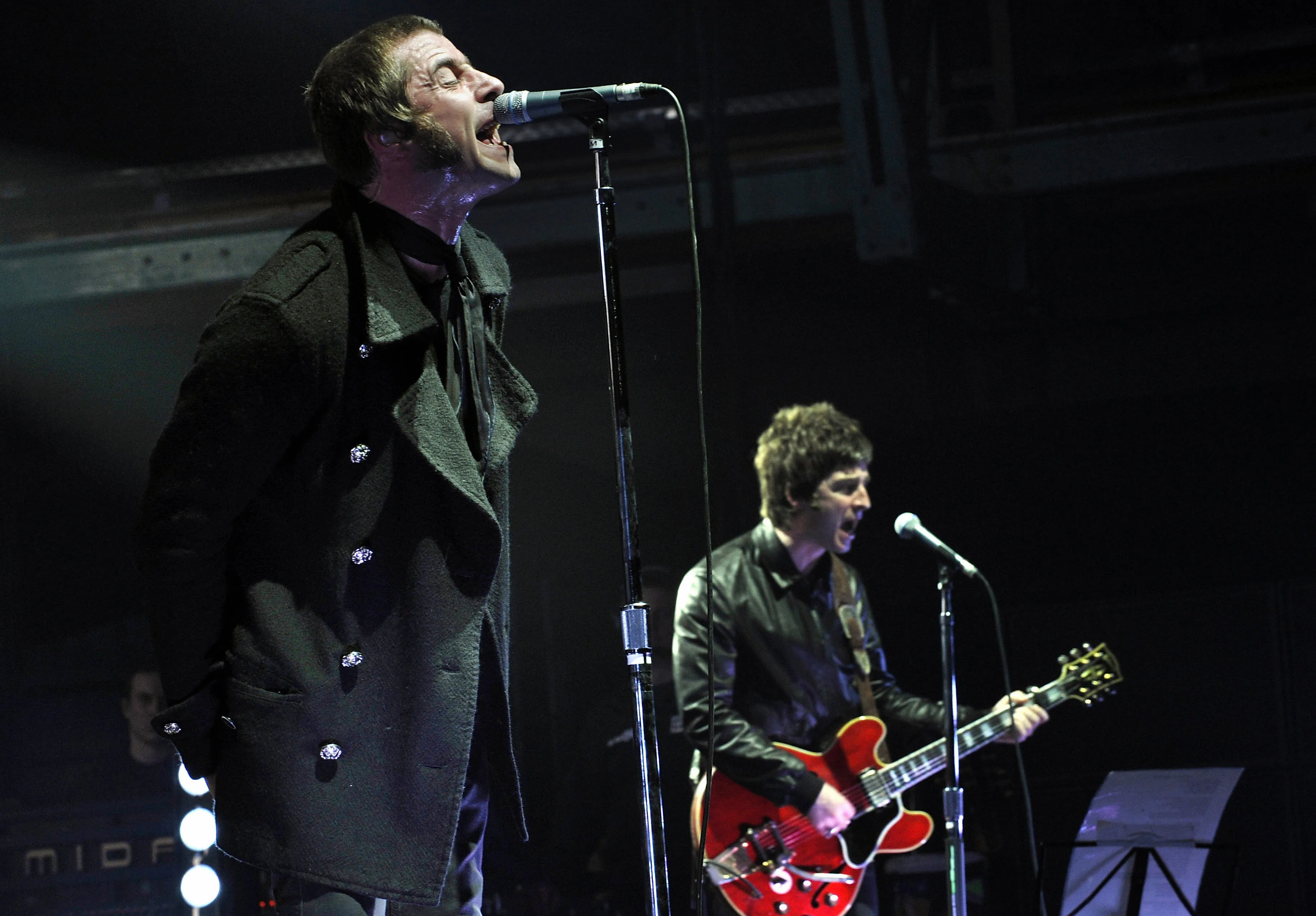

Anyone who has searched for a flight or an Uber ride is probably used to seeing the advertised price change before they actually come to book it. But this phenomenon of “dynamic” pricing is not widely known to apply to concert seats. Fans of Oasis discovered it on Saturday, when the cost of tickets for the British rock group’s comeback tour more than doubled in the space of a few hours. UK Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy said it was “depressing to see vastly inflated prices excluding ordinary fans,” and promised to examine dynamic pricing as part of a government probe into ticket selling. Here’s how dynamic pricing works, and why it’s become so widespread.

What is dynamic pricing?

Also known as yield management and surge pricing, dynamic pricing is a modern adaptation of the old rules of supply and demand — only applied in real-time thanks to technology. Instead of re-evaluating prices yearly or quarterly, companies can now adjust them almost instantly to make sure they secure the highest price that buyers are willing to pay at any point in time. In the case of the Oasis concerts, basic standing tickets were initially advertised at around £150 ($197), but rose to £355 after a few hours as fans rushed to the ticketing websites.

How does dynamic pricing work?

Companies selling anything online can see what people have been buying at what price and estimate future demand with growing accuracy thanks to recent advances in commercial software, some of it driven by artificial intelligence. They use marketing tools, trackers and algorithms to adjust prices, often with little or no human intervention. With dynamic pricing, prices can go up but also come down if demand wanes.

Which businesses use dynamic pricing?

Early versions of dynamic pricing emerged in the 1990s, when increasingly powerful computer systems allowed airlines to begin adjusting their fares automatically to make sure they filled their planes. The rise of e-commerce triggered a race to develop more sophisticated dynamic pricing, encouraging more widespread adoption. It’s now used for selling holidays, hotel rooms, tickets for trains and theme parks and a vast array of consumer goods. Online retailers such as Amazon.com Inc. adjust price tags on products automatically depending on demand and other factors, including the prices and discounts advertised by competitors, or the weather. Dynamic pricing for concerts is more recent and has been used largely for big-demand events such as Bruce Springsteen and Harry Styles gigs. Some mobile apps have made surge pricing more transparent, with ride-hailing platforms such as Uber signaling temporary surcharges to customers when local factors like rain lead to a jump in demand. The online advertising industry uses dynamic pricing to manage inventory, and even the housing industry has been adopting rent-maximizing software.

Is dynamic pricing fair?

Dynamic pricing is under growing scrutiny. In the US, the Federal Trade Commission has encouraged regulators to be vigilant as AI pricing algorithms can facilitate collusive behavior that unfairly inflates prices. The US Congress proposed legislation earlier this year to prevent anticompetitive conduct through pricing algorithms. The practice is fair in the case of a concert, in the sense that people are not going to pay too high a price if there is no demand, said Schellion Horn, a partner at accounting and consulting firm Grant Thornton. But altering prices dramatically without warning consumers in advance raises potential issues around transparency and consumer protection, she said. More essential goods — especially those subject to a monopoly, such as water — generally can’t be sold using dynamic pricing as the prices are regulated. Food retailers and restaurants have so far been reluctant to use dynamic pricing, as such an aggressive tactic is seen as inappropriate when selling something as vital as food. In February, Wendy’s Chief Executive Officer Kirk Tanner told analysts that the fast-food chain would test dynamic pricing, before back-tracking when his comments sparked a consumer backlash on social media.

Can you avoid getting stung by dynamic pricing?

It’s not easy. Even buying travel tickets early is no guarantee of getting the lowest price as prices can go down as well as up, said Horn at Grant Thornton. But there are websites to compare prices across different sellers over time and alert buyers when it’s the best moment to buy. In the case of high-demand events like concerts or sports events, being a member of a fan club can often give early or preferred access. In the UK and France, tennis club members can buy cheaper tickets to Wimbledon or the French Open through ballots or pre-sales.